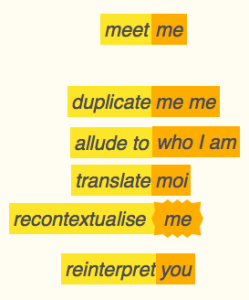

(In response to Walter Mulch’s In the Blink of an Eye: A Perspective on Film Editing.)

So you make yourself comfortable in the well-equiped editing room, whether in the physical sense or whatever computing setup you use as your virtual editing room. Besides you lies a hundred feet or so worth of film, or alternatively, your computer screen flickers with hundreds of freshly-DSLR’d shots of close ups, tight shots, and context-establishing sequences.

You feel the heaviness of the weight of the director’s original vision, whatever it might be, and which is often, in itself, a subjective take on the essence of a script and/or original source material, and the potential enjoyment (or lack thereof) of all prospective film viewers.

To prepare yourself for the elusivity of the high-stakes process of film editing, you summon a “cheatsheet” of sorts that, supposedly, distills the process of film editing. Its contents, if they are of any merit, will most likely be along the following lines.

1. Remind yourself that the process of editing is a process of pathfinding. You start with no inherent guarantees of what the end product will end up like, but you do know that it will be what it is supposed to be. Shots, in their rawest form are sturctureless, and what you do is to find or synthesise a path towards a coherently fulfilled vision.

2. Know that the process of cutting is not just that, it is an extensive, iterative process of decision making as to what constitutes a suitable cut, and what can be put aside as a “shadow” cut, regardless of all the effort that went to it. Editing is a process that is measured in quality, not quantity.

3. Be aware of the reason why (almost) all films need to be cut: Because of the logistic impossibility of having all objects, all actors, and all suitable conditions in the same place to construct a complete film in a single shot. In a way, by overcoming this limitation, filmmakers are freed from the impossibility of controlling every gesture or condition simultaneously to get a perfectly-coherent film.

4. Recall that editing is not simply “taking out the bad bits,” but more of giving a film its unique nature through the order you bestow upon it. The shots are the DNA and the editing is the sequencing of it.

5. Get your priorities straight: you should edit for emotion, then narrative, then rhythm. Lower in importance are the viewer’s eye-trace, the stage-line, and the 3D space continuity of the shot. Minimize the compromise you make for the first (tightly-bound) three as much as possible.

6. Think like the viewer, and direct, or misdirect, him or her towards your narrative through editing. Minute details are most of the time indiscernible to the viewer. (To help you keep that in mind at all time, you may use a cutout stick figure as a visual representation of the proportion of the cinema-goer against the towering cinema screen.)

7. Isolate yourself from the conditions of shooting. All effort, time, cost, and agony that went into a shot are irrelevant if they do not perfect the emotional impact, progress the story, or fit into the rhythm of the film.

8. Engage in editing in a pair or more, part of it is to avoid a locked POV on what should or should not be there, and the other part is to meet the often unforgiving timelines. One of you can be the “dreamer,” while the other will have to challenge the validity of the other’s dream.

9. Visually distill each of the shots into a single “decisive moment,” preferably as a physically printed shot, that can both illuminate the emotion of a shot, and be used as a linguistic representation of all the details it can encompass.

10. Conduct test screenings with an audience, but don’t take their explicit feedback to heart. Instead, focus on how does it feel to show your edited film to an audience. If you must collect explicit feedback, be sure that it is a good time after the screening, so as to get a fully formed impression, not a reaction, or a referred pain, where the reaction is driven by a single scene when the issue is in what leads to or follows from it.

11. Think of cuts as a blink of an eye amidst one’s continuously perceived reality: it happens when one thought gives way to another, when one emotion overtakes the observer in a way that changes his perception of the moment. Alternatively, think of an edited film as a dream where cuts happen to compress time and space in a meaningful, not necessarily realistic way.

12. For any scene, there is a finite number of possible good cuts, which results in a specific branching schema that the editor has to bring to his awareness. The meaning of this is that not every moment is a potential cut; if, say, you want your audience to perceive a speaker as a liar, there is only one appropriate cut for that. An earlier or a later cut will result in the misdirection of the audience towards another conclusion.